This is one of the wonderful stories of events from the Trans-Tasman Race. As everybody might enjoy a break from my writing, I am going to let the words of Terry Hammond, who was the navigator for Leda’s crew during the race tell this tale.

It will need to be rotated in your viewer.

“WOULDN”T HAVE HAPPENED IN A 747

The Year was 1951, and TEAL (Tasman Empire Airways Limited), now Air New Zealand , operated the Trans-Tasman route from New Zealand to Australia with Short Solent flying boats. This continued a long tradition, dating from before World War II , of flying boat operation. During the war, almost the only link between the two countries was provided by just two modified Empire class flying boats – the usual surface ships on the route had been pressed into wartime service – and the result was a long standing love affair between the people of New Zealand and these magnificent machines.

The Solent Mk IV was the culmination of a long line, and was a delightful aircraft for both passengers and crew. All up weight was 81,000 pounds, and it was powered by four 2040 HP Bristol Hercules engines. It had two decks, and part of the upper one was devoted to a large and comfortable flight deck. Someone once said that “you could hold a dance on the navigator’s table”, and that was only a slight exaggeration! The flight crew comprised two pilots, a navigator, radio operator, and flight engineer.

The galley could almost have served a small apartment, and meals were cooked there in flight.

Passenger accommodation was equally spacious, and was divided into separate cabins, with most of the seats facing fixed tables for meals or card games during flight. The aircraft was not pressurised and so was able to have large windows providing great views There was even a stand-up bar on the upper deck – and this was over 60 years ago.

Now Auckland , often called the “City of Sails,” is the home of yachting in New Zealand, and sailing has for many years been a major sport. Back in those post-war years, one of the toughest races anywhere in the world was the Trans-Tasman race, sailed across the Tasman Sea which lies between New Zealand and Australia, and is often a notoriously stormy stretch of ocean. In January the race was scheduled to be sailed from Auckland to Sydney, a total distance of about 1280 nautical miles or 2,370 kilometres. The course was from Auckland, up the east coast of New Zealand to the northern tip, and then almost 1100 miles west across the Tasman to Sydney.

For this race I had come from Australia to join the crew of “Leda” as navigator, crew hand , and radio operator.

“Leda” was a very beautiful 54 footer, lovingly built of timber over four years by two brothers, Sandy and Dooley Wilson, and for the race was carrying a crew of eight, including the wives of Sandy and Dooley, Erica and Kit. She was one of the favourites to finish first, although the official winner was to be determined by a handicap system to give the smaller boats an equal chance.

Sandy was a reporter on an Auckland newspaper, and his paper had requested that we radio them daily reports on the progress of the race.

To enable this we had a more powerful radio than normally carried by small boats of that time – long before the days of compact solid state transmitters. Most small radios could transmit on only a few fixed frequencies, but we had acquired a powerful ex aircraft system, a Collins Autotune, which could be set on any frequency within its range. This was to prove vital in what eventuated during the following days

The race started on January 21 1951, and it was two days later when Leda rounded the northern tip of New Zealand and headed west towards Australia, in remarkably benign conditions with light winds and gentle seas. However on that day we suffered a catastrophic gear failure – we broke our only can opener !! We were saved from imminent starvation only by judicious use of a substantial sailor’s knife, but found that to be a messy and inconvenient procedure, specially for our lady crew members.

Just one of the hardships of ocean racing!

Early next morning we were well out of sight of land, on our way across the Tasman, when we heard the sound of an aircraft engines, and high above us we recognised one of TEAL’s flying boats.

We thought it might be interesting to try to contact them by radio, but the problem was that aircraft and small yachts work on different frequencies and so they would not hear us if we called them. However by a lucky fluke of memory I could recall the frequency used by Auckland air traffic control, and quickly tuned our transmitter to 6557 kc/sec (hadn’t heard of kilohertz in those days),

and started “calling the flying boat that just passed over a yacht”. We assumed that they could have seen us, as they were flying below 10000 feet, not being pressurized, and we had set a large brightly coloured sail.

Somewhat to our surprise the reply came back “ Hello Leda, this is ZKAMA, flying boat “Ararangi”, receiving you loud and clear”. Unfortunately we also heard another signal, from Auckland air radio, telling us in no uncertain terms to get off their frequency. This we promptly did, but not before telling the aircraft our proper marine channel, and getting their normal operating frequency, so we were able to continue our contact. Of course by this time they were a hundred miles or more away from us, but it was reassuring to talk to them. They asked if there was anything they could do for us, in the way of passing on messages or such, and just as a joking remark, I suggested that we could do with a new can opener. There was no comment from them, but before closing the contact I made arrangements to keep a schedule with the west bound flight the next day. I should state here that due to the fact that it was about a seven hour flight from Auckland to Sydney, and they normally did not fly at night, it would be a different aircraft leaving Auckland the following day. However they said they would pass the message back to New Zealand.

This they must have done, because right on 9 AM the next morning, after our “calling a TEAL flying boat”, back came the answer “Leda, this is ZKAMN, “Awatere”, replying.”

Then the contact went a little as follows – “Leda, have you got an accurate position?”

“Yes, we got some good star sights this morning and so have a good position”

(Remember, there was no such thing as GPS then, or even Loran in that part of the world, and the sextant was our only way to get a good position)

We passed on our latitude and longitude, and got the reply “OK Leda, we’ll come up and have a look for you”

And right on time, there they were, high up in the east. We saw them first, called them up and gave them their compass bearing from us.

“OK Leda, we’ve got you now, and we’re coming down to have a look”

So down they came, until they were just above our masthead height, and circled round us in both directions so the passengers on both sides could have a good look.

We must have been a great sight, as it was a beautiful day, and we had our huge brightly coloured spinnaker set.

Then came the surprise –

“Oh, by the way Leda, we’ve got your can opener for you !”

And off they flew to the north, and then flew back across our bow. Just before they got to us we saw a small parcel come out of the plane, with a long streamer attached to make it visible. It was a beautiful shot, and landed in the water dead ahead of us, less than fifty feet away. We fished it out of the water with a boathook as we passed, and there it was – an old lifejacket for floatation, and a small plastic wrapped parcel. Great excitement on deck as we opened it- TWO can openers, and a copy of the morning paper from Auckland.

With our thanks, and a wiggle of its wings, the giant flying boat climbed away on its course to Sydney.

So there we were – on a small sailing yacht in the middle of the ocean, sitting there reading the morning paper delivered courtesy of a commercial passenger airliner – not to mention the now neatly opened cans.

Later we realised that the accurate “bombing” shot should have been no surprise, for many of the TEAL captains would have flown Sunderlands – a wartime predecessor of the Solent – in the Coastal Command during the war, and would have gained experience dropping depth charges on U-Boats.

We had made arrangements to radio the aircraft each day as we headed towards Sydney, and quite a few interesting conversations followed.

The weather was uncharacteristically benign, and I guess that driving a flying boat across the Tasman in good weather was getting boring at times, and other aircrews wanted to get in on the act, so the upshot was that in the next nine days we had the morning paper delivered seven times !

We were asked if there was anything else we needed, and the single ones on board suggested that four “air hostesses” (in those days the term for stewardess or flight attendant) would be a pleasant addition to our crew, but sadly they were unable to oblige – perhaps no parachutes!

One captain remarked – “looks a lovely day down there – maybe I could land in the water and take half your crew into “Sammy Lees” (a notorious Sydney night club) for the night, and drop you back on the eastbound flight in the morning” Sadly he was only joking.

Of course with all the passengers on these flights, and the great interest in the yacht race back in New Zealand, it wasn’t long before the details of these goings on were reported in the news, and one morning we were interested to read in our freshly delivered paper, that a spokesman for the Department of Civil Aviation (NZ equivalent of the FAA) had said “ of course these aircraft would not be permitted to leave their normal course just to fly over the yachts. However weather conditions in the Tasman of late have been forcing them to fly north of their usual track “ !!

In fact that was not just “official speak”, but quite logical. A relatively slow aircraft would find it an advantage to look for following winds, and at the time a large “high” in the Tasman was producing easterly winds north of their usual direct track. That also accounted for the fact that we saw only the westbound flights, and not the returning ones.

However all good things – and good weather – come to an end, and as we neared Sydney we encountered near gale force winds and rough seas. This actually suited us quite well, as “Leda” performed very well in these conditions and we were leading the fleet as we approached land.

It was here that we had our last aerial contact, and the aircraft we were talking to gave us some unsolicited information – “Sydney Heads bears 273 degrees, 53 miles from your position”

This was heard by another yacht, which caused us some embarrassment, as a strict rule of ocean racing says that no outside help or advice is permitted (can openers aren’t considered to count)

However the race committee ruled that as the advice was unsolicited, and as also that our log book showed that we were well aware of our position anyway, no action would be taken.

We finally entered Sydney harbour on the afternoon of February 7, to a great welcome, as we were the first boat in. A smaller boat (“Solveig”) actually won the prize on handicap, but we were still very happy with our voyage – and of course all the fun with the aircraft added to the excitement – and the public interest

One foot note

Years later, sitting in an Air New Zealand jet, flying across the Tasman, I requested the steward to ask the captain if he had ever flown flying boats. An invitation to the flight deck quickly followed (no terrorists in those days) and it turned out that he had in fact been a junior officer on one of the actual paper drops.

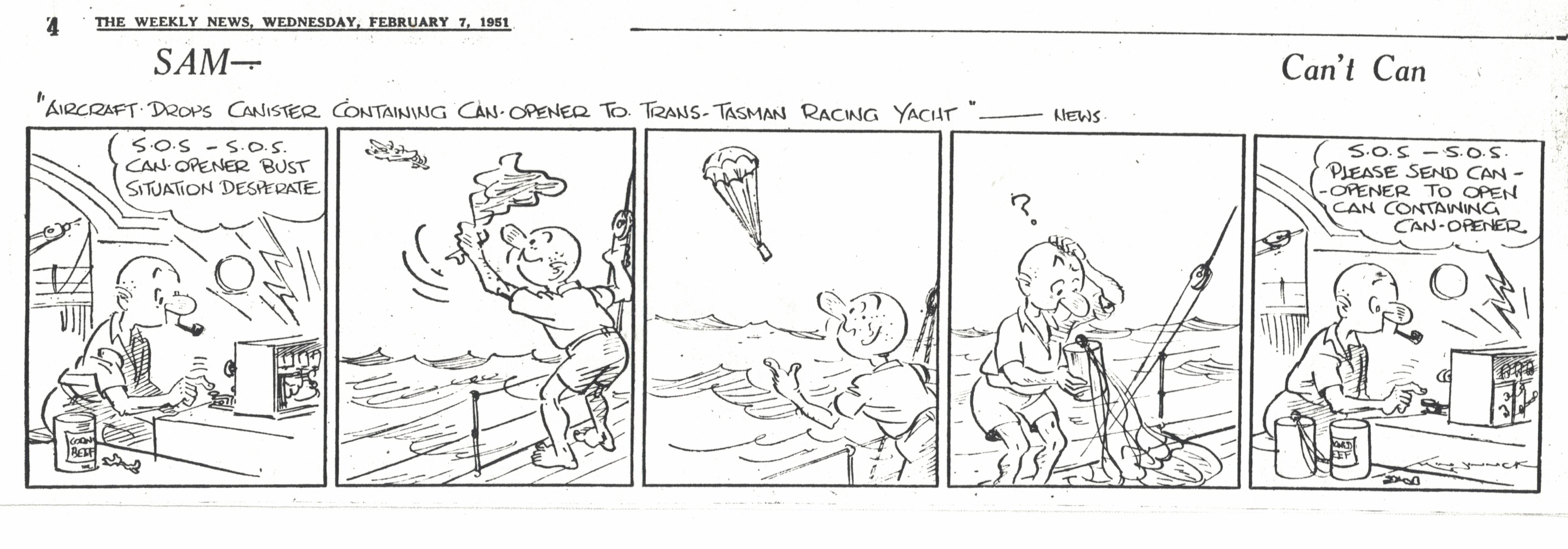

The attached cartoon appeared in the paper during our voyage. “Sam” was a regular figure in a local comic strip, and one of the newspaper reports had (wrongly) stated that the can opener had been dropped in “a sealed canister beneath a small parachute” – and of course our radio contact had been by voice and not by Morse code.

Also on one of the paper drops the captain said that he had forgotten to prepare our paper, and at the last moment had got two copies from the passengers (in those days a complimentary copy was given to each passenger, and in a hurry he had just wrapped one inside another and tossed them out the window. Aim was so good that we picked them up before the inside one had even got wet.!

On receiving outside help – we were well aware of the rules, and were quite happy that the can opener would not cause any trouble. However we had a sewing machine on board for light sail repairs, such as spinnakers, and later in the voyage found that the casualty rate among needles had been high, but we definitely would not have asked for replacements, as that would certainly be considered as outside assistance.

Over the years I had been able to find occasional references to Leda on the internet. Sandy and Dooley had sailed her to America and sold her there. While there,Sandy joined the crew of a yacht sailing from San Francisco to Los Angeles, which was run down by a freighter in heavy fog, and sadly all the yacht’s crew were lost.

I eventually tracked down the current owner of Leda, and found that she had been well restored and was moored in Alaska, in Tee Harbor, a few miles north of Juneau. I was able to start a very pleasant email conversation with Russ, the owner of the boat and it was great to learn that Leda was in such good and loving hands. After the Tasman race, one of our trophies was a handsome engraved mug presented to the first New Zealand boat to finish, and I was delighted when Sandy gave it to me as a memento of a great voyage. I thought that it would fitting that the trophy stayed with the boat, so I sent it to Russ, together with copies of some newspaper cuttings from 1951, and he was delighted to add them to other items connected with the yacht.

That might have been the end of the story, until in 2010 I fulfilled a long held wish to cruise Alaskan waters, and booked a cruise on a small tourist vessel. It transpired that the voyage started and finished in Juneau, and when Russ learned of this, he and Ginny were waiting at Juneau airport to welcome Ann and me to Alaska. They were wonderful hosts and of course we were delighted to see Leda looking so good almost 60 years after her Tasman crossing. When the cruise boat returned to Juneau, we stayed with them, and it hardly needs saying that the highlight was sailing in Alaskan waters on this beautiful yacht.

It is almost impossible to describe how I felt at the wheel once again , after so many years and so many great memories

Thank you, Russ and Ginny, and thank you too, Leda.”

And thank you Terry. It was a wonderful treat for us to have Ann and Terry as guests on board Leda. It was also a treat to listen to Terry’s stories. We sat in my house below a bookshelf full of books about sailing and boats while he told stories of sailing with the Smeetons or Adlard Coles. He wasn’t dropping names. He had no one to impress, he was just telling good sea stories. All the while I found it fascinating that I could look at my book shelf and see the spines of legendary nonfiction sailing books by these same names.

Terry went on from navigating the Trans-Tasman to a life full of sailing adventures. He was navigator for Australia’s first challenge for the America’s Cup on board Gretel in 1962. He became a color commentator for ESPN in Australia during the cup matches in later years. He was also the official measurer for the yacht club in Brisbane where he made his home.

Terry and Ann on board Leda outside Tee Harbor Alaska, 2010

Terry told me during his trip to Alaska that, after all these years (and so many boats), Leda was still his favorite yacht. That is quite a compliment.

Further reading on Terry Hammond be be found here: Veteran sailor was sharp navigator

Terry’s telling of the Can Opener Incident was kindly sent to me by his partner, Ann Mills, an accomplished sailor in her own right.